History of Afro-American Music 1PART I

|

Ragtime'First musical genre born in America'

Ragtime (alternatively spelled rag-time or rag time) is a musical genre that enjoyed its peak popularity between 1897 and 1918. Its main characteristic trait is its syncopated, or "ragged," rhythm. It began as dance music in the red-light districts of African American communities in St. Louis and New Orleans years before being published as popular sheet music for piano. Ernest Hogan was an innovator and key pioneer who helped develop the musical genre, and is credited with coining the term ragtime. Ragtime was also a modification of the march made popular by John Philip Sousa, with additional polyrhythms coming from African music.The ragtime composer Scott Joplin became famous through the publication in 1899 of the "Maple Leaf Rag" and a string of ragtime hits such as "The Entertainer" that followed, although he was later forgotten by all but a small, dedicated community of ragtime aficionados until the major ragtime revival in the early 1970s. For at least 12 years after its publication, the "Maple Leaf Rag" heavily influenced subsequent ragtime composers with its melody lines, harmonic progressions or metric patterns.

Ragtimen tausta-The birth of Ragtime

Orjuuden lopettaminen 1800-luvun puolivälissä antoi vapautetuille afrikanamerikkalaisille uusia mahdollisuuksia myös kouluttautumiseen. Vaikka tiukat rotulait estivätkin monesti mustien työllistymisen, löysivät silti monet töitä viihdealalta. Mustat muusikot saattoivat saada 'alemman kastin' keikkoja esim. minstrel show ja vaudeville -esityksissä, jolloin myös monet 'marssiyhtyeet' muodostuivat. Pianistit (usein afrikanamerikkalaiset) esiintyivät baareissa, klubeissa ja bordelleissa ragtimen kehittyessä.

"Ragtime originated in African American music in the late 19th century, descending from the jigs and march music played by black bands.[13] By the start of the 20th century, it became widely popular throughout North America and was listened and danced to, performed, and written by people of many different subcultures. A distinctly American musical style, ragtime may be considered a synthesis of African syncopation and European classical music, especially the marches made popular by John Philip Sousa."

Ragtime (alternatively spelled rag-time or rag time) is a musical genre that enjoyed its peak popularity between 1897 and 1918. Its main characteristic trait is its syncopated, or "ragged," rhythm. It began as dance music in the red-light districts of African American communities in St. Louis and New Orleans years before being published as popular sheet music for piano. Ernest Hogan was an innovator and key pioneer who helped develop the musical genre, and is credited with coining the term ragtime. Ragtime was also a modification of the march made popular by John Philip Sousa, with additional polyrhythms coming from African music.The ragtime composer Scott Joplin became famous through the publication in 1899 of the "Maple Leaf Rag" and a string of ragtime hits such as "The Entertainer" that followed, although he was later forgotten by all but a small, dedicated community of ragtime aficionados until the major ragtime revival in the early 1970s. For at least 12 years after its publication, the "Maple Leaf Rag" heavily influenced subsequent ragtime composers with its melody lines, harmonic progressions or metric patterns.

Ragtimen tausta-The birth of Ragtime

Orjuuden lopettaminen 1800-luvun puolivälissä antoi vapautetuille afrikanamerikkalaisille uusia mahdollisuuksia myös kouluttautumiseen. Vaikka tiukat rotulait estivätkin monesti mustien työllistymisen, löysivät silti monet töitä viihdealalta. Mustat muusikot saattoivat saada 'alemman kastin' keikkoja esim. minstrel show ja vaudeville -esityksissä, jolloin myös monet 'marssiyhtyeet' muodostuivat. Pianistit (usein afrikanamerikkalaiset) esiintyivät baareissa, klubeissa ja bordelleissa ragtimen kehittyessä.

"Ragtime originated in African American music in the late 19th century, descending from the jigs and march music played by black bands.[13] By the start of the 20th century, it became widely popular throughout North America and was listened and danced to, performed, and written by people of many different subcultures. A distinctly American musical style, ragtime may be considered a synthesis of African syncopation and European classical music, especially the marches made popular by John Philip Sousa."

The "Black Codes" outlawed drumming by slaves. Therefore, unlike in Cuba, Haiti, and elsewhere in the Caribbean, African drumming traditions were not preserved in North America. African-based rhythmic patterns were retained in the United States in large part, through "body rhythms" such as stomping, clapping, and patting juba. Robert Palmer states: "The patting, an ex-slave reported in 1853, 'is performed by striking the right shoulder with one hand, the left hand with the other—all while keeping time with the feet, and singing.'" African Americans also used everyday household items as percussion instruments. Anthropologist David Evans did extensive fieldwork in the hill country of northern Mississippi, and reports of black families playing polyrhythmic music in their homes on chairs, tin cans, and empty bottles.

There are examples of tresillo, or tresillo-like rhythms in a few surviving nineteenth-century African American folk musics, such as patting juba, and the clapping and foot stomping patterns in ring shout. Palmer describes the foot-generated music:

Accounts ... leave little doubt that the dancing and stamping constituted a kind of drumming, especially when the worshippers had a wooden church floor to stamp on. "It always rouses my imagination," wrote Lydia Parrish of the Georgia Sea Islands in 1942, "to see the way in which the McIntosh County 'shouters' tap their heels on the resonant floor to imitate the beat of the drum their forebears were not allowed to have."[37]

There are examples of tresillo, or tresillo-like rhythms in a few surviving nineteenth-century African American folk musics, such as patting juba, and the clapping and foot stomping patterns in ring shout. Palmer describes the foot-generated music:

Accounts ... leave little doubt that the dancing and stamping constituted a kind of drumming, especially when the worshippers had a wooden church floor to stamp on. "It always rouses my imagination," wrote Lydia Parrish of the Georgia Sea Islands in 1942, "to see the way in which the McIntosh County 'shouters' tap their heels on the resonant floor to imitate the beat of the drum their forebears were not allowed to have."[37]

Two decades after drumming was banned in Congo Square, in the post-Civil War period (after 1865), African Americans were able to obtain surplus military bass drums, snare drums and fifes. As a result, an original African American drum and fife music arose, featuring tresillo and related syncopated rhythmic figures.[38] With this music genre, we see the emergence of a drumming tradition that is distinct from its Caribbean counterparts, expressing a sensibility that is uniquely African American. Evans states that among the older black drum and fife musicians of northern Mississippi, making the drums "talk it"—that is, playing rhythm patterns that conform to proverbial phrases or the words of popular fife and drum tunes—"is considered the sign of a good drummer."[39] Palmer observes: "The snare and bass drummers played syncopated cross-rhythms," and speculates—"this tradition must have dated back to the latter half of the nineteenth century, and it could have not have developed in the first place if there hadn't been a reservoir of polyrhythmic sophistication in the culture it nurtured."[39]

Tresillo is heard prominently in New Orleans second line music, and in most every other form of popular music to come out of that city from the turn of the twentieth century to present. Jazz historian Gunther Schuller states: "It is probably safe to say that by and large the simpler African rhythmic patterns survived in jazz ... because they could be adapted more readily to European rhythmic conceptions. Some survived, others were discarded as the Europeanization progressed. It may also account for the fact that patterns such as [tresillo have] ... remained one of the most useful and common syncopated patterns in jazz."

"Spanish tinge"—the Afro-Cuban rhythmic influence

A candombe scene in Montevideo, 1870.

African American music began incorporating Afro-Cuban rhythmic motifs in the nineteenth century, when the habanera (Cuban contradanza) gained international popularity.[42] Habaneras were widely available as sheet music. The habanera was the first written music to be rhythmically based on an African motif (1803).[43] From the perspective of African American music, the habanera rhythm (also known as congo,[44] tango-congo, or tango.[46]) can be thought of as a combination of tresillo and the backbeat.

African American music began incorporating Afro-Cuban rhythmic motifs in the nineteenth century, when the habanera (Cuban contradanza) gained international popularity.[42] Habaneras were widely available as sheet music. The habanera was the first written music to be rhythmically based on an African motif (1803).[43] From the perspective of African American music, the habanera rhythm (also known as congo,[44] tango-congo, or tango.[46]) can be thought of as a combination of tresillo and the backbeat.

Habanera rhythm written as a combination of tresillo (bottom notes) with the backbeat (top note). Play

Musicians from Havana and New Orleans would take the twice-daily ferry between both cities to perform and not surprisingly, the habanera quickly took root in the musically fertile Crescent City. The habanera was the first of many Cuban music genres which enjoyed periods of popularity in the United States, and reinforced and inspired the use of tresillo-based rhythms in African American music.

John Storm Roberts states that the musical genre habanera, "reached the U.S. twenty years before the first rag was published."[48] The piano piece "Ojos Criollos (Danse Cubaine)" (1860) by New Orleans native Louis Moreau Gottschalk, was influenced by the composer's studies in Cuba. The habanera rhythm is clearly heard in the left hand.[49] With Gottschalk's symphonic work "A Night in the Tropics" (1859), we hear the tresillo variant cinquillo extensively.[50] The figure was also used by Scott Joplin and other ragtime composers.

Musicians from Havana and New Orleans would take the twice-daily ferry between both cities to perform and not surprisingly, the habanera quickly took root in the musically fertile Crescent City. The habanera was the first of many Cuban music genres which enjoyed periods of popularity in the United States, and reinforced and inspired the use of tresillo-based rhythms in African American music.

John Storm Roberts states that the musical genre habanera, "reached the U.S. twenty years before the first rag was published."[48] The piano piece "Ojos Criollos (Danse Cubaine)" (1860) by New Orleans native Louis Moreau Gottschalk, was influenced by the composer's studies in Cuba. The habanera rhythm is clearly heard in the left hand.[49] With Gottschalk's symphonic work "A Night in the Tropics" (1859), we hear the tresillo variant cinquillo extensively.[50] The figure was also used by Scott Joplin and other ragtime composers.

Cinquillo. Play

For the more than quarter-century in which the cakewalk, ragtime, and proto-jazz were forming and developing, the habanera was a consistent part of African American popular music.[51] Comparing the music of New Orleans with the music of Cuba, Wynton Marsalis observes that tresillo is the New Orleans "clave", a Spanish word meaning 'code,' or 'key'—as in the key to a puzzle, or mystery.[52] Although technically, the pattern is only half a clave, Marsalis makes the important point that the single-celled figure is the guide-pattern of New Orleans music. Jelly Roll Morton called the rhythmic figure the Spanish tinge, and considered it an essential ingredient of jazz.[53]

Musiikkibisnes näihin aikoihin oli keskittynyt nuottien kustannukseen ja suurimmat hitit olivat kin esim. pianokappaleita joita saatettiin myydä tuhansiakin. Niin myös ragtime tuli tunnetuksi myös nuottien kautta, jotka olivat afrikanamerikkalaisten muusikoiden tunnetuksi tekemiä. Yksi tällainen esimerkki on Ernest Hogan ( Ernest Reuben Crowdus; 1865 – May 20, 1909[),josta myöhemmin tuli ensimmäinen afrikanamerikkalainen joka tuotti - ja esiintyi itse tähtenä Broadway-showssa. Hoganin hittikappaleet 'La Pas Ma La' ja 'All Coons Look Alike Me' ilmestyivät vuonna 1895. Jälkimmäinen näistä sai ideansa erään chicagolaisen pianistin esittämästä kappaleesta 'All Pimps Look Alike Me'. 'Coon' sana oli rasistinen ilmaisu mustaihoisesta, ja monet esiintyjät jo jättivät sen (sanan) pois esityksissään, koska pitivät ilmaisua halventavana ja tuon ajan stereotypioita korostavana. Kappaletta myytiin joka tapauksessa miljoonia.Myöhemmin Hogan sanoi katuvansa stereotyypioiden vahvistamista ja 'kansansa pettämistä'.

For the more than quarter-century in which the cakewalk, ragtime, and proto-jazz were forming and developing, the habanera was a consistent part of African American popular music.[51] Comparing the music of New Orleans with the music of Cuba, Wynton Marsalis observes that tresillo is the New Orleans "clave", a Spanish word meaning 'code,' or 'key'—as in the key to a puzzle, or mystery.[52] Although technically, the pattern is only half a clave, Marsalis makes the important point that the single-celled figure is the guide-pattern of New Orleans music. Jelly Roll Morton called the rhythmic figure the Spanish tinge, and considered it an essential ingredient of jazz.[53]

Musiikkibisnes näihin aikoihin oli keskittynyt nuottien kustannukseen ja suurimmat hitit olivat kin esim. pianokappaleita joita saatettiin myydä tuhansiakin. Niin myös ragtime tuli tunnetuksi myös nuottien kautta, jotka olivat afrikanamerikkalaisten muusikoiden tunnetuksi tekemiä. Yksi tällainen esimerkki on Ernest Hogan ( Ernest Reuben Crowdus; 1865 – May 20, 1909[),josta myöhemmin tuli ensimmäinen afrikanamerikkalainen joka tuotti - ja esiintyi itse tähtenä Broadway-showssa. Hoganin hittikappaleet 'La Pas Ma La' ja 'All Coons Look Alike Me' ilmestyivät vuonna 1895. Jälkimmäinen näistä sai ideansa erään chicagolaisen pianistin esittämästä kappaleesta 'All Pimps Look Alike Me'. 'Coon' sana oli rasistinen ilmaisu mustaihoisesta, ja monet esiintyjät jo jättivät sen (sanan) pois esityksissään, koska pitivät ilmaisua halventavana ja tuon ajan stereotypioita korostavana. Kappaletta myytiin joka tapauksessa miljoonia.Myöhemmin Hogan sanoi katuvansa stereotyypioiden vahvistamista ja 'kansansa pettämistä'.

The controversy over the song has, to some degree, caused Hogan to be overlooked as one of the originators of ragtime, which has been called the first truly American musical genre. Hogan's songs were among the first published ragtime songs and the first to use the term "rag" in their sheet music copy. While Hogan made no claims to having exclusively created ragtime, fellow Black musician Tom Fletcher said Hogan was the "first to put on paper the kind of rhythm that was being played by non-reading musicians." When the ragtime championship was held as part of the 1900 World Competition in New York, semifinalists played Hogan's "All Coons Look Alike to Me" to prove their skill.

Vuonna 1897 Vess Osmann - 5-kielisen banjon soittaja (ja myöhemmin myös levyttävä artisti) levytti banjolla esitetyn medleyn Hoganin kappaleista - 'Rag Time Medleyn'. Samana vuonna valkoihoinen säveltäjä William H. Krell sävelsi 'Missisippi Rag' -kappaleen jota pidetään ensimmäisenä instrumentaalikappaleena ragtime-tyyliin sävellettynä. Samoihin aikoihin Tom Turpin julkaisi ensimmäisenä afrikanamerikkalaisena oman sävellyksensä. Kappaleen nimi oli 'Harlem Rag' ja se itse asiassa sävellettiin jo vuonna 1892, vuotta ennen 1893 'World Fair' (Maailmannäyttelyä).Turpin sävelsi myös useita muita, menestyviä kappaleita ja omisti muun muassa oman saluunan St. Louis:ssa, Missourissa. Myöhemmin Turpinia kutsuttiin myös 'kunnianimellä' 'Father of St. Louis Ragtime'

Vuonna 1897 Vess Osmann - 5-kielisen banjon soittaja (ja myöhemmin myös levyttävä artisti) levytti banjolla esitetyn medleyn Hoganin kappaleista - 'Rag Time Medleyn'. Samana vuonna valkoihoinen säveltäjä William H. Krell sävelsi 'Missisippi Rag' -kappaleen jota pidetään ensimmäisenä instrumentaalikappaleena ragtime-tyyliin sävellettynä. Samoihin aikoihin Tom Turpin julkaisi ensimmäisenä afrikanamerikkalaisena oman sävellyksensä. Kappaleen nimi oli 'Harlem Rag' ja se itse asiassa sävellettiin jo vuonna 1892, vuotta ennen 1893 'World Fair' (Maailmannäyttelyä).Turpin sävelsi myös useita muita, menestyviä kappaleita ja omisti muun muassa oman saluunan St. Louis:ssa, Missourissa. Myöhemmin Turpinia kutsuttiin myös 'kunnianimellä' 'Father of St. Louis Ragtime'

Scott Joplin

The classically trained pianist Scott Joplin (c. 1867/1868 – April 1, 1917) and the acknowledged "king of ragtime" produced his "Original Rags" in the following year, then in 1899 had an international hit with "Maple Leaf Rag". "Maple Leaf Rag" is a multi-strain ragtime march with athletic bass lines and offbeat melodies. Each of the four parts features a recurring theme and a striding bass line with copious seventh chords. The piece may be considered the 'archetypal rag' due to its influence on the genre; its structure was the basis for many other famous rags, including "Sensation" by Joseph Lamb. It is more carefully constructed than almost all the previous rags, and the syncopations in the right hand, especially in the transition between the first and second strain, were novel at the time.

|

Excerpt from "Maple Leaf Rag" by Scott Joplin (1899). Seventh chord resolution. Play (help·info). Note that the seventh resolves down by half step.

African-based rhythmic patterns, such as tresillo, and its variants—the habanera rhythm and cinquillo, are heard in the ragtime compositions of Scott Joplin, Tom Turpin, and others. Joplin's "Solace" (1909) is generally considered to be within the habanera genre (although it's labeled a "Mexican serenade").[44][60] The following excerpt from "Solace" is based on two different variants of the habanera rhythm. |

Excerpt from "Solace" by Scott Joplin (1909). Variations on the habanera rhythm.

With "Solace" both hands are playing in a syncopated fashion, completely abandoning any sense of a march rhythm. Ned Sublette postulates that the tresillo/habanera rhythm "found its way into ragtime and the cakewalk,"[61] while Roberts suggests that "the habanera influence may have been part of what freed black music from ragtime's European bass."[

Joplin wrote numerous popular rags, including "The Entertainer", combining right hand tresillo-based syncopation, banjo figurations and sometimes call-and-response. The ragtime idiom was eventually taken up by classical composers including Claude Debussy and Igor Stravinsky.

Joplin wrote numerous popular rags, including "The Entertainer", combining right hand tresillo-based syncopation, banjo figurations and sometimes call-and-response. The ragtime idiom was eventually taken up by classical composers including Claude Debussy and Igor Stravinsky.

MUSICAL FORM OF RAGTIME/MUSIIKILLINEN MUOTO RAGTIMESSA

The first page of "The Easy Winners" by Scott Joplin, showing ragtime rhythms and syncopated melodies.

The rag was a modification of the march made popular by John Philip Sousa, with additional polyrhythms coming from African music.[5] It was usually written in 2/4 or 4/4 time with a predominant left-hand pattern of bass notes on strong beats (beats 1 and 3) and chords on weak beats (beat 2 and 4) accompanying a syncopated melody in the right hand. According to some sources the name "ragtime" may come from the "ragged or syncopated rhythm" of the right hand.[2] A rag written in 3/4 time is a "ragtime waltz."

Ragtime is not a "time" (meter) in the same sense that march time is 2/4 meter and waltz time is 3/4 meter; it is rather a musical genre that uses an effect that can be applied to any meter. The defining characteristic of ragtime music is a specific type of syncopation in which melodic accents occur between metrical beats. This results in a melody that seems to be avoiding some metrical beats of the accompaniment by emphasizing notes that either anticipate or follow the beat ("a rhythmic base of metric affirmation, and a melody of metric denial"[21]). The ultimate (and intended) effect on the listener is actually to accentuate the beat, thereby inducing the listener to move to the music. Scott Joplin, the composer/pianist known as the "King of Ragtime", called the effect "weird and intoxicating." He also used the term "swing" in describing how to play ragtime music: "Play slowly until you catch the swing...".[22] The name swing later came to be applied to an early genre of jazz that developed from ragtime. Converting a non-ragtime piece of music into ragtime by changing the time values of melody notes is known as "ragging" the piece. Original ragtime pieces usually contain several distinct themes, four being the most common number. These themes were typically 16 bars, each theme divided into periods of four four-bar phrases and arranged in patterns of repeats and reprises. Typical patterns were AABBACCC′, AABBACCDD and AABBCCA, with the first two strains in the tonic key and the following strains in the subdominant. Sometimes rags would include introductions of four bars or bridges, between themes, of anywhere between four and 24 bars

Ragtime is not a "time" (meter) in the same sense that march time is 2/4 meter and waltz time is 3/4 meter; it is rather a musical genre that uses an effect that can be applied to any meter. The defining characteristic of ragtime music is a specific type of syncopation in which melodic accents occur between metrical beats. This results in a melody that seems to be avoiding some metrical beats of the accompaniment by emphasizing notes that either anticipate or follow the beat ("a rhythmic base of metric affirmation, and a melody of metric denial"[21]). The ultimate (and intended) effect on the listener is actually to accentuate the beat, thereby inducing the listener to move to the music. Scott Joplin, the composer/pianist known as the "King of Ragtime", called the effect "weird and intoxicating." He also used the term "swing" in describing how to play ragtime music: "Play slowly until you catch the swing...".[22] The name swing later came to be applied to an early genre of jazz that developed from ragtime. Converting a non-ragtime piece of music into ragtime by changing the time values of melody notes is known as "ragging" the piece. Original ragtime pieces usually contain several distinct themes, four being the most common number. These themes were typically 16 bars, each theme divided into periods of four four-bar phrases and arranged in patterns of repeats and reprises. Typical patterns were AABBACCC′, AABBACCDD and AABBCCA, with the first two strains in the tonic key and the following strains in the subdominant. Sometimes rags would include introductions of four bars or bridges, between themes, of anywhere between four and 24 bars

The styles of Ragtime

Ragtime pieces came in a number of different styles during the years of its popularity and appeared under a number of different descriptive names. It is related to several earlier styles of music, has close ties with later styles of music, and was associated with a few musical "fads" of the period such as the foxtrot. Many of the terms associated with ragtime have inexact definitions, and are defined differently by different experts; the definitions are muddled further by the fact that publishers often labelled pieces for the fad of the moment rather than the true style of the composition. There is even disagreement about the term "ragtime" itself; experts such as David Jasen and Trebor Tichenor choose to exclude ragtime songs from the definition but include novelty piano and stride piano (a modern perspective), while Edward A. Berlin includes ragtime songs and excludes the later styles (which is closer to how ragtime was viewed originally). The terms below should not be considered exact, but merely an attempt to pin down the general meaning of the concept.

- Cakewalk – a pre-ragtime dance form popular until about 1904. The music is intended to be representative of an African-American dance contest in which the prize is a cake. Many early rags are cakewalks.

- Characteristic march – a march incorporating idiomatic touches (such as syncopation) supposedly characteristic of the race of their subject, which is usually African-Americans. Many early rags are characteristic marches.

- Two-step – a pre-ragtime dance form popular until about 1911. A large number of rags are two-steps.

- Slow drag – another dance form associated with early ragtime. A modest number of rags are slow drags.

- Coon song – a pre-ragtime vocal form popular until about 1901. A song with crude, racist lyrics often sung by white performers in blackface. Gradually died out in favor of the ragtime song. Strongly associated with ragtime in its day, it is one of the things that gave ragtime a bad name.

- Ragtime song – the vocal form of ragtime, more generic in theme than the coon song. Though this was the form of music most commonly considered "ragtime" in its day, many people today prefer to put it in the "popular music" category. Irving Berlin was the most commercially successful composer of ragtime songs, and his "Alexander's Ragtime Band" (1911) was the single most widely performed and recorded piece of this sort, even though it contains virtually no ragtime syncopation. Gene Greene was a famous singer in this style.

- Folk ragtime – a name often used to describe ragtime that originated from small towns or assembled from folk strains, or at least sounded as if they did. Folk rags often have unusual chromatic features typical of composers with non-standard training.

- Classic rag – a name used to describe the Missouri-style ragtime popularized by Scott Joplin, James Scott, and others.

- Fox-trot – a dance fad that began in 1913. Fox-trots contain a dotted-note rhythm different from that of ragtime, but which nonetheless was incorporated into many late rags.

- Novelty piano – a piano composition emphasizing speed and complexity, which emerged after World War I. It is almost exclusively the domain of white composers.

- Stride piano – a style of piano that emerged after World War I, developed by and dominated by black East-coast pianists (James P. Johnson, Fats Waller and Willie 'The Lion' Smith). Together with novelty piano, it may be considered a successor to ragtime, but is not considered by all to be "genuine" ragtime. Johnson composed the song that is arguably most associated with the Roaring Twenties, "Charleston." A recording of Johnson playing the song appears on the compact disc James P. Johnson: Harlem Stride Piano (Jazz Archives No. 111, EPM, Paris, 1997). Johnson's recorded version has a ragtime flavor.

Questionnair/assignments

Answer the following questions:

- When and where was Ragtime born?

- When did Ragtime enjoy it's peak popularity?

- Mention 6 different Ragtime composers and 10 different compositions

- What was the rhythmic background of ragtime? What about the harmonic background?

- Mention 6 different styles of Ragtime

- Explain the terms: 'Stride piano' , 'Charleston', 'Tresillo', 'Habanera', 'Cinquillo'

- Explain a typical Ragtime song form: Length (how many measures each part), Parts (how many, which order), Key changes

Thanks a lot for your responses! I'll be waiting..

PART II: THE BLUES

Blues is the name given to both a musical form and a music genre[1] that originated in African-American communities of primarily the "Deep South" of the United States around the end of the 19th century from spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts and chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads.[2] The blues form, ubiquitous in jazz, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll is characterized by specific chord progressions, of which the twelve-bar blues chord progression is the most common. The blue notes that, for expressive purposes are sung or played flattened or gradually bent (minor 3rd to major 3rd) in relation to the pitch of the major scale, are also an important part of the sound. (Wikipedia)

The Origins of the Blues

Little is known about the exact origin of the music now known as the blues.[1] No specific year can be cited as the origin of the blues, largely because the style evolved over a long period and existed in approaching its modern form before the term blues was introduced, before the style was thoroughly documented.Ethnomusicologist Gerhard Kubik traces the roots of many of the elements that were to develop into the blues back to the African continent, the "cradle of the blues".[2] One important early mention of something closely resembling the blues comes from 1901, when an archaeologist in Mississippi described the songs ofblack workers which had lyrical themes and technical elements in common with the blues.[3] (Wikipedia)

"Long before the blues became recognized as a distinct style of music, it lived a subterranean existence in African American communities. The blues would not emerge as a major force in the recording industry until the 1920s, but persistent scholars have uncovered earlier traces and hints of the music throughout the former slave states going back to the nineteenth century, especially in geographic settings with a high proportion of black sharecroppers and farmworkers. Unlike jazz, which first came to New Orleans and flourished in other large cities, early blues found its most fertile breeding ground in rural areas and the most impoverished parts of the country. This humble lineage is all the more ironic when one considers how much the financial well-being of the later entertainment industry in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, London, and elsewhere would depend on this rustic music and its many offshoots in rock, R&B, funk and other associated urban genres.

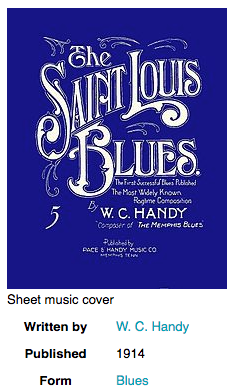

Blues songs began appearing in sheet music form as early as 1912, none with more staying power than W.C.Handy's "St. Louis Blues" (1914), which would rank as the second most recorded song of the first half of the twentieth century, surpassed only by "Silent Night". The term blues - often misused to refer to any sad or mournful tune - is more properly linked, as we see in Handy's composition, to a precise structure that has come to be known as blues form. This repeating twelve-bar pattern is typically built on three chords-- tonic, subdominant and dominant-- and would later serve as a widely used recipe for rock-n-roll and R&B music. When sung, as it usually was in its earliest variants, the blues also employs a specific stanza for its lyrics in which an initial line is stated, repeated , and then followed with a rhyming line. For example, Handy's "St. Louis Blues" begins:

I hate to see that evenin' sun go down

I hate to see the evenin' sun go down

'Cause my baby, he done lef' this town.

Yet this type of lyric and chord patterns are not sufficient to convey the essence of the blues. the most characteristic component of this music is found in its distinctive melodic mines, which emphasize the so-called blue notes : often described as the use of both the major and minor third in the vocal line, along with the flatted seventh: the flatted fifth was a later addition, but would in time become equally prominent as a blue note. In truth, this 'stock description' is also somewhat misleading. In early blues, the major and minor thirds were not used interchangeably; instead the musician might employ a 'bent' note that would slide between these two notes, or create a tension by emphasizing the minor third in a context in which the harmony implied a major tone. Sometimes this effect was acheived by means of a melismatic shift in the voice of the blues singer, but even instrumentalists made use of this approach----most strikingly int he slide guitar techniques that relied on moving a bottle, knife, ot other objects across the fingerboard to stretch the individual pitches. After the arival of blues, notes were no longer just notes, but flexible sounds that could change in ways unforeseen by the most renowned nineteenth-century composers....

The most traditional style of blues typically relies on just a vocal line with guitar accompaniment. Handy was inspired by just such performance back in the Mississippi Delta, when he heard a raggedy musician playing a guitar with a knife at a train station in Tutwitler, circa 1903. But this minimalist style of performance, often referred to as 'country blues', was slow in finding its way onto recordings. Not until late 1920s, with the commercial success of Blind lemon Jefferson, born near Wortham, texas, in the closing years of the nineteenth century, employed a spare, riff-oriented guitar style behind his droning and resonant vocalizing. Although he was capable of raspy, low tones, his voice was perhaps most admired for its thin, high tones--- a stylistic device that, for many listeners, stands out as the most distinctive characteristic of the early Texas blues sound. Jefferson recorded around one hundred tracks for the Paramount label from 1926 through 1929, and his performances of songs such as 'Long Lonesome Blues', Matchbox Blues', and 'See That My Grave Is Kept Clean' continue to delight fans even today. Despite the efforts of various researchers, this artist's life remains clouded in mystery, and even the circumstances of his death are a matter of contentious speculation...." (Ted Gioia: the History of Jazz)

The Origins of the Blues

Little is known about the exact origin of the music now known as the blues.[1] No specific year can be cited as the origin of the blues, largely because the style evolved over a long period and existed in approaching its modern form before the term blues was introduced, before the style was thoroughly documented.Ethnomusicologist Gerhard Kubik traces the roots of many of the elements that were to develop into the blues back to the African continent, the "cradle of the blues".[2] One important early mention of something closely resembling the blues comes from 1901, when an archaeologist in Mississippi described the songs ofblack workers which had lyrical themes and technical elements in common with the blues.[3] (Wikipedia)

"Long before the blues became recognized as a distinct style of music, it lived a subterranean existence in African American communities. The blues would not emerge as a major force in the recording industry until the 1920s, but persistent scholars have uncovered earlier traces and hints of the music throughout the former slave states going back to the nineteenth century, especially in geographic settings with a high proportion of black sharecroppers and farmworkers. Unlike jazz, which first came to New Orleans and flourished in other large cities, early blues found its most fertile breeding ground in rural areas and the most impoverished parts of the country. This humble lineage is all the more ironic when one considers how much the financial well-being of the later entertainment industry in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, London, and elsewhere would depend on this rustic music and its many offshoots in rock, R&B, funk and other associated urban genres.

Blues songs began appearing in sheet music form as early as 1912, none with more staying power than W.C.Handy's "St. Louis Blues" (1914), which would rank as the second most recorded song of the first half of the twentieth century, surpassed only by "Silent Night". The term blues - often misused to refer to any sad or mournful tune - is more properly linked, as we see in Handy's composition, to a precise structure that has come to be known as blues form. This repeating twelve-bar pattern is typically built on three chords-- tonic, subdominant and dominant-- and would later serve as a widely used recipe for rock-n-roll and R&B music. When sung, as it usually was in its earliest variants, the blues also employs a specific stanza for its lyrics in which an initial line is stated, repeated , and then followed with a rhyming line. For example, Handy's "St. Louis Blues" begins:

I hate to see that evenin' sun go down

I hate to see the evenin' sun go down

'Cause my baby, he done lef' this town.

Yet this type of lyric and chord patterns are not sufficient to convey the essence of the blues. the most characteristic component of this music is found in its distinctive melodic mines, which emphasize the so-called blue notes : often described as the use of both the major and minor third in the vocal line, along with the flatted seventh: the flatted fifth was a later addition, but would in time become equally prominent as a blue note. In truth, this 'stock description' is also somewhat misleading. In early blues, the major and minor thirds were not used interchangeably; instead the musician might employ a 'bent' note that would slide between these two notes, or create a tension by emphasizing the minor third in a context in which the harmony implied a major tone. Sometimes this effect was acheived by means of a melismatic shift in the voice of the blues singer, but even instrumentalists made use of this approach----most strikingly int he slide guitar techniques that relied on moving a bottle, knife, ot other objects across the fingerboard to stretch the individual pitches. After the arival of blues, notes were no longer just notes, but flexible sounds that could change in ways unforeseen by the most renowned nineteenth-century composers....

The most traditional style of blues typically relies on just a vocal line with guitar accompaniment. Handy was inspired by just such performance back in the Mississippi Delta, when he heard a raggedy musician playing a guitar with a knife at a train station in Tutwitler, circa 1903. But this minimalist style of performance, often referred to as 'country blues', was slow in finding its way onto recordings. Not until late 1920s, with the commercial success of Blind lemon Jefferson, born near Wortham, texas, in the closing years of the nineteenth century, employed a spare, riff-oriented guitar style behind his droning and resonant vocalizing. Although he was capable of raspy, low tones, his voice was perhaps most admired for its thin, high tones--- a stylistic device that, for many listeners, stands out as the most distinctive characteristic of the early Texas blues sound. Jefferson recorded around one hundred tracks for the Paramount label from 1926 through 1929, and his performances of songs such as 'Long Lonesome Blues', Matchbox Blues', and 'See That My Grave Is Kept Clean' continue to delight fans even today. Despite the efforts of various researchers, this artist's life remains clouded in mystery, and even the circumstances of his death are a matter of contentious speculation...." (Ted Gioia: the History of Jazz)

St. Louis Blues - 9 bars, tenor saxophone

Analysis of "St. Louis Blues"The form is unusual in that the verses are the now familiar standard twelve-bar blues in common time with three lines of lyrics, the first two lines repeated, but it also has a 16-bar bridge written in the habanera rhythm, popularly called the "Spanish Tinge", and identified by Handy as tango[6] Handy's tango-like rhythm is notated as a dotted quarter note, followed by an eighth, and two quarter notes, with no slurs or ties, and is seen in the introduction as well as the sixteen-measure bridge.[7]

Excerpt from "St. Louis Blues" by W.C. Handy (1914). The left hand plays the habanera rhythm.While blues became often simple and repetitive in form, "Saint Louis Blues" has multiple complementary and contrasting strains, similar to classic ragtimecompositions. Handy said his objective in writing "Saint Louis Blues" was "to combine ragtime syncopation with a real melody in the spiritual tradition."[8]

The first publication of blues sheet music was in 1908: Antonio Maggio's "I Got the Blues" is the first published song to use the word blues. Hart Wand's "Dallas Blues" followed in 1912; W. C. Handy's "The Memphis Blues" followed in the same year. The first recording by an African American singer was Mamie Smith's 1920 rendition of Perry Bradford's "Crazy Blues". But the origins of the blues date back to some decades earlier, probably around 1890.[33] They are very poorly documented, due in part to racial discrimination within American society, including academic circles,[34] and to the low literacy rate of the rural African American community at the time.[35]

Chroniclers began to report about blues music in Southern Texas and Deep South at the dawn of the 20th century. In particular, Charles Peabody mentioned the appearance of blues music at Clarksdale, Mississippi and Gate Thomas reported very similar songs in southern Texas around 1901–1902. These observations coincide more or less with the remembrance of Jelly Roll Morton, who declared having heard blues for the first time in New Orleans in 1902; Ma Rainey, who remembered her first blues experience the same year in Missouri; and W.C. Handy, who first heard the blues in Tutwiler, Mississippi in 1903. The first extensive research in the field was performed by Howard W. Odum, who published a large anthology of folk songs in the counties of Lafayette, Mississippi and Newton, Georgia between 1905 and 1908.[36] The first non-commercial recordings of blues music, termed "proto-blues" by Paul Oliver, were made by Odum at the very beginning of the 20th century for research purposes. They are now utterly lost.[37]

Other recordings that are still available were made in 1924 by Lawrence Gellert. Later, several recordings were made byRobert W. Gordon, who became head of the Archive of American Folk Songs of the Library of Congress. Gordon's successor at the Library was John Lomax. In the 1930s, together with his son Alan, Lomax made a large number of non-commercial blues recordings that testify to the huge variety of proto-blues styles, such as field hollers and ring shouts.[38] A record of blues music as it existed before the 1920s is also given by the recordings of artists such asLead Belly[39] or Henry Thomas[40] who both performed archaic blues music. All these sources show the existence of many different structures distinct from the twelve-, eight-, or sixteen-bar.[41][42]

The first publication of blues sheet music was in 1908: Antonio Maggio's "I Got the Blues" is the first published song to use the word blues. Hart Wand's "Dallas Blues" followed in 1912; W. C. Handy's "The Memphis Blues" followed in the same year. The first recording by an African American singer was Mamie Smith's 1920 rendition of Perry Bradford's "Crazy Blues". But the origins of the blues date back to some decades earlier, probably around 1890.[33] They are very poorly documented, due in part to racial discrimination within American society, including academic circles,[34] and to the low literacy rate of the rural African American community at the time.[35]

Chroniclers began to report about blues music in Southern Texas and Deep South at the dawn of the 20th century. In particular, Charles Peabody mentioned the appearance of blues music at Clarksdale, Mississippi and Gate Thomas reported very similar songs in southern Texas around 1901–1902. These observations coincide more or less with the remembrance of Jelly Roll Morton, who declared having heard blues for the first time in New Orleans in 1902; Ma Rainey, who remembered her first blues experience the same year in Missouri; and W.C. Handy, who first heard the blues in Tutwiler, Mississippi in 1903. The first extensive research in the field was performed by Howard W. Odum, who published a large anthology of folk songs in the counties of Lafayette, Mississippi and Newton, Georgia between 1905 and 1908.[36] The first non-commercial recordings of blues music, termed "proto-blues" by Paul Oliver, were made by Odum at the very beginning of the 20th century for research purposes. They are now utterly lost.[37]

Other recordings that are still available were made in 1924 by Lawrence Gellert. Later, several recordings were made byRobert W. Gordon, who became head of the Archive of American Folk Songs of the Library of Congress. Gordon's successor at the Library was John Lomax. In the 1930s, together with his son Alan, Lomax made a large number of non-commercial blues recordings that testify to the huge variety of proto-blues styles, such as field hollers and ring shouts.[38] A record of blues music as it existed before the 1920s is also given by the recordings of artists such asLead Belly[39] or Henry Thomas[40] who both performed archaic blues music. All these sources show the existence of many different structures distinct from the twelve-, eight-, or sixteen-bar.[41][42]

John Lomax, pioneering musicologistand folklorist.The social and economic reasons for the appearance of the blues are not fully known.[43] The first appearance of the blues is often dated after the Emancipation Act of 1863,[34] between 1870 and 1900, a period that coincides withEmancipation and, later, the development of juke joints as places where Blacks went to listen to music, dance, or gamble after a hard day's work.[44] This period corresponds to the transition from slavery to sharecropping, small-scale agricultural production, and the expansion of railroads in the southern United States. Several scholars characterize the early 1900s development of blues music as a move from group performances to a more individualized style. They argue that the development of the blues is associated with the newly acquired freedom of the enslaved people.[45]

According to Lawrence Levine, "there was a direct relationship between the national ideological emphasis upon the individual, the popularity of Booker T. Washington's teachings, and the rise of the blues." Levine states that "psychologically, socially, and economically, African-Americans were being acculturated in a way that would have been impossible during slavery, and it is hardly surprising that their secular music reflected this as much as their religious music did."[45]

There are few characteristics common to all blues music, because the genre took its shape from the idiosyncrasies of individual performances.[46] However, there are some characteristics that were present long before the creation of the modern blues. Call-and-response shouts were an early form of blues-like music; they were a "functional expression ... style without accompaniment or harmony and unbounded by the formality of any particular musical structure."[47] A form of this pre-blues was heard in slave ring shouts and field hollers, expanded into "simple solo songs laden with emotional content".[48]

Blues has evolved from the unaccompanied vocal music and oral traditions of slaves imported from West Africa and rural blacks into a wide variety of styles and subgenres, with regional variations across the United States. Though blues, as it is now known, can be seen as a musical style based on both European harmonic structure and the African call-and-response tradition, transformed into an interplay of voice and guitar,[49][50] the blues form itself bears no resemblance to the melodic styles of the West African griots, and the influences are faint and tenuous.[51][52]

In particular, no specific African musical form can be identified as the single direct ancestor of the blues.[53] However many blues elements, such as the call-and-response format and the use of blue notes, can be traced back to the music of Africa. That blue notes pre-date their use in blues and have an African origin is attested by English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's "A Negro Love Song", from his The African Suite for Piano composed in 1898, which contains blue thirdand seventh notes.[54] (Wikipedia/Blues)

The African roots of the blues

African American work songs were an important precursor to the modern blues; these included the songs sung by laborers like stevedores and roustabouts, and thefield hollers and "shouts" of slaves.[3][4]

There are few characteristics common to all blues, as the genre takes its shape from the peculiarities of each individual performance.[5] Some characteristics, however, were present prior to the creation of the modern blues, and are common to most styles of African American music. The earliest blues-like music was a "functional expression, rendered in a call-and-response style without accompaniment or harmony and unbounded by the formality of any particular musical structure".[6] This pre-blues music was adapted from the field shouts and hollers performed during slave times, expanded into "simple solo songs laden with emotional content".[7]

There are few characteristics common to all blues, as the genre takes its shape from the peculiarities of each individual performance.[5] Some characteristics, however, were present prior to the creation of the modern blues, and are common to most styles of African American music. The earliest blues-like music was a "functional expression, rendered in a call-and-response style without accompaniment or harmony and unbounded by the formality of any particular musical structure".[6] This pre-blues music was adapted from the field shouts and hollers performed during slave times, expanded into "simple solo songs laden with emotional content".[7]

Many of these blues elements, such as the call-and-response format, can be traced back to the music of Africa. The use of melisma and a wavy, nasal intonation also suggests a connection between the music of West and Central Africa and the blues. The belief that blues is historically derived from the West African music including from Mali is reflected in Martin Scorsese’s often quoted characterization of Ali Farka Touré’s tradition as constituting "the DNA of the blues"[8]

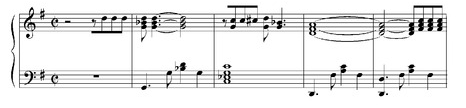

The Jola akonting folk lutePerhaps the most compelling African instrument that is a predecessor to an African-American instrument is the "Akonting", a folk lute of the Jola tribe ofSenegambia. It is a clear predecessor to the American banjo in its playing style, the construction of the instrument itself and in its social role as a folk instrument. The Kora is played by a professional caste of praise singers for the rich and aristocracy (called griots or jalis) and is not considered folk music. Jola music was actually not influenced much by Islamic and North African/Middle Eastern music, and this may give us an important clue as to how African American music does not, according to many scholars such as Sam Charters, bear hardly any relation to kora music. Rather, African-American music may reflect a hold over from a pre-Islamicized form of African music. The music of the Akonting and that played by on the banjo by elder African-American banjo players, even into the mid 20th century is easily identified as being very similar. The akonting is perhaps the most important and concrete link that exists between African and African-American music.

However, while the findings of Kubik and others also clearly attest to the essential Africanness of many essential aspects of blues expression, studies byWillie Ruff and others have situated the origin of "black" spiritual music inside enslaved peoples' exposure to their masters'Hebridean-originated gospels.[9] African-American economist and historian Thomas Sowell also notes that the southern, black, ex-slave population was acculturated to a considerable degree by and among their Scots-Irish "redneck" neighbours.

The Jola akonting folk lutePerhaps the most compelling African instrument that is a predecessor to an African-American instrument is the "Akonting", a folk lute of the Jola tribe ofSenegambia. It is a clear predecessor to the American banjo in its playing style, the construction of the instrument itself and in its social role as a folk instrument. The Kora is played by a professional caste of praise singers for the rich and aristocracy (called griots or jalis) and is not considered folk music. Jola music was actually not influenced much by Islamic and North African/Middle Eastern music, and this may give us an important clue as to how African American music does not, according to many scholars such as Sam Charters, bear hardly any relation to kora music. Rather, African-American music may reflect a hold over from a pre-Islamicized form of African music. The music of the Akonting and that played by on the banjo by elder African-American banjo players, even into the mid 20th century is easily identified as being very similar. The akonting is perhaps the most important and concrete link that exists between African and African-American music.

However, while the findings of Kubik and others also clearly attest to the essential Africanness of many essential aspects of blues expression, studies byWillie Ruff and others have situated the origin of "black" spiritual music inside enslaved peoples' exposure to their masters'Hebridean-originated gospels.[9] African-American economist and historian Thomas Sowell also notes that the southern, black, ex-slave population was acculturated to a considerable degree by and among their Scots-Irish "redneck" neighbours.

Early blues

Blue notes pre-date their use in blues. English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's "A Negro Love Song", from his The African Suite for Piano composed in 1898, contains blue third and seventh notes.[14]

African American composer W. C. Handy wrote in his autobiography of the experience of sleeping on a train traveling through (or stopping at the station of) Tutwiler, Mississippi around 1903, and being awakened by:

... a lean, loose-jointed Negro [who] had commenced plucking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings in a manner popularised by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. ... The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly... The singer repeated the line ("Goin' where the Southern cross' the Dog") three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.

Handy had mixed feelings about this music, which he regarded as rather primitive and monotonous,[15] but he used the "Southern cross' the Dog" line in his 1914 "Yellow Dog Rag", which he retitled "Yellow Dog Blues" after the term blues became popular.[16] "Yellow Dog" was the nickname of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad.

Blues later adopted elements from the "Ethiopian (here, meaning "black") airs" of minstrel shows and Negro spirituals, including instrumental and harmonic accompaniment.[17] The style also was closely related to ragtime, which developed at about the same time, though the blues better preserved "the original melodic patterns of African music".[18]

Since the 1890s, the American sheet music publishing industry had produced a great deal of ragtime music. The first published ragtime song to include a 12-bar section was "One o' Them Things!" in 1904. Written by James Chapman and Leroy Smith, it was published in St. Louis, Missouri, by Jos. Plachet and Son.[19]Another early rag/blues mix was "I Got The Blues" published in 1908 by Anthony Maggio of New Orleans [20]

In a long interview conducted by Alan Lomax in 1938, Jelly Roll Morton recalled that the first blues he had heard, probably around 1900, was played by a singer and prostitute, Mamie Desdunes, in Garden District, New Orleans. Morton sang the blues: "Can’t give me a dollar, give me a lousy dime/ You can’t give me a dollar, give me a lousy dime/ Just to feed that hungry man of mine". The interview was released as The Complete Library of Congress Recordings.[21]

African American composer W. C. Handy wrote in his autobiography of the experience of sleeping on a train traveling through (or stopping at the station of) Tutwiler, Mississippi around 1903, and being awakened by:

... a lean, loose-jointed Negro [who] had commenced plucking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings in a manner popularised by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. ... The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly... The singer repeated the line ("Goin' where the Southern cross' the Dog") three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.

Handy had mixed feelings about this music, which he regarded as rather primitive and monotonous,[15] but he used the "Southern cross' the Dog" line in his 1914 "Yellow Dog Rag", which he retitled "Yellow Dog Blues" after the term blues became popular.[16] "Yellow Dog" was the nickname of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad.

Blues later adopted elements from the "Ethiopian (here, meaning "black") airs" of minstrel shows and Negro spirituals, including instrumental and harmonic accompaniment.[17] The style also was closely related to ragtime, which developed at about the same time, though the blues better preserved "the original melodic patterns of African music".[18]

Since the 1890s, the American sheet music publishing industry had produced a great deal of ragtime music. The first published ragtime song to include a 12-bar section was "One o' Them Things!" in 1904. Written by James Chapman and Leroy Smith, it was published in St. Louis, Missouri, by Jos. Plachet and Son.[19]Another early rag/blues mix was "I Got The Blues" published in 1908 by Anthony Maggio of New Orleans [20]

In a long interview conducted by Alan Lomax in 1938, Jelly Roll Morton recalled that the first blues he had heard, probably around 1900, was played by a singer and prostitute, Mamie Desdunes, in Garden District, New Orleans. Morton sang the blues: "Can’t give me a dollar, give me a lousy dime/ You can’t give me a dollar, give me a lousy dime/ Just to feed that hungry man of mine". The interview was released as The Complete Library of Congress Recordings.[21]

In the 1920s, the blues became a major element of African American and American popular music, reaching white audiences via Handy's arrangements and the classic female blues performers. The blues evolved from informal performances in bars to entertainment in theaters. Blues performances were organized by the Theater Owners Bookers Association in nightclubs such as the Cotton Club and juke joints such as the bars along Beale Street in Memphis. Several record companies, such as theAmerican Record Corporation, Okeh Records, and Paramount Records, began to record African American music.

As the recording industry grew, country blues performers like Bo Carter, Jimmie Rodgers (country singer), Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, Tampa Red and Blind Blake became more popular in the African American community. Kentucky-born Sylvester Weaver was in 1923 the first to record the slide guitar style, in which a guitar is fretted with a knife blade or the sawed-off neck of a bottle.[68] The slide guitar became an important part of the Delta blues.[69] The first blues recordings from the 1920s are categorized as a traditional, rural country blues and a more polished 'city' or urban blues.

As the recording industry grew, country blues performers like Bo Carter, Jimmie Rodgers (country singer), Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, Tampa Red and Blind Blake became more popular in the African American community. Kentucky-born Sylvester Weaver was in 1923 the first to record the slide guitar style, in which a guitar is fretted with a knife blade or the sawed-off neck of a bottle.[68] The slide guitar became an important part of the Delta blues.[69] The first blues recordings from the 1920s are categorized as a traditional, rural country blues and a more polished 'city' or urban blues.

Country blues performers often improvised, either without accompaniment or with only a banjo or guitar. Regional styles of country blues varied widely in the early 20th century. The (Mississippi) Delta blues was a rootsy sparse style with passionate vocals accompanied by slide guitar. The little-recorded Robert Johnson[70] combined elements of urban and rural blues. In addition to Robert Johnson, influential performers of this style included his predecessors Charley Patton and Son House. Singers such as Blind Willie McTell and Blind Boy Fuller performed in the southeastern "delicate and lyrical" Piedmont blues tradition, which used an elaborate ragtime-based fingerpicking guitar technique. Georgia also had an early slide tradition,[71] with Curley Weaver, Tampa Red, "Barbecue Bob" Hicks and James "Kokomo" Arnold as representatives of this style.[72]

The lively Memphis blues style, which developed in the 1920s and 1930s near Memphis, Tennessee, was influenced by jug bands such as the Memphis Jug Band or the Gus Cannon's Jug Stompers. Performers such as Frank Stokes, Sleepy John Estes, Robert Wilkins, Joe McCoy, Casey Bill Weldon and Memphis Minnie used a variety of unusual instruments such as washboard, fiddle, kazoo or mandolin. Memphis Minnie was famous for her virtuoso guitar style. Pianist Memphis Slim began his career in Memphis, but his distinct style was smoother and had some swing elements. Many blues musicians based in Memphis moved to Chicago in the late 1930s or early 1940s and became part of the urban blues movement, which blended country music and electric blues.

The lively Memphis blues style, which developed in the 1920s and 1930s near Memphis, Tennessee, was influenced by jug bands such as the Memphis Jug Band or the Gus Cannon's Jug Stompers. Performers such as Frank Stokes, Sleepy John Estes, Robert Wilkins, Joe McCoy, Casey Bill Weldon and Memphis Minnie used a variety of unusual instruments such as washboard, fiddle, kazoo or mandolin. Memphis Minnie was famous for her virtuoso guitar style. Pianist Memphis Slim began his career in Memphis, but his distinct style was smoother and had some swing elements. Many blues musicians based in Memphis moved to Chicago in the late 1930s or early 1940s and became part of the urban blues movement, which blended country music and electric blues.

Urban blues

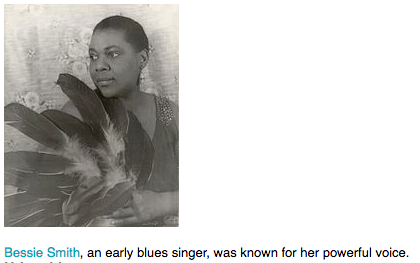

City or urban blues styles were more codified and elaborate as a performer was no longer within their local, immediate community and had to adapt to a larger, more varied audience's aesthetic.[75] Classic female urban and vaudeville blues singers were popular in the 1920s, among them Mamie Smith, Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Victoria Spivey. Mamie Smith, more a vaudeville performer than a blues artist, was the first African-American to record a blues in 1920; her second record, "Crazy Blues", sold 75,000 copies in its first month.[76]

Ma Rainey, the "Mother of Blues", and Bessie Smith each "[sang] around center tones, perhaps in order to project her voice more easily to the back of a room." Smith would "... sing a song in an unusual key, and her artistry in bending and stretching notes with her beautiful, powerful contralto to accommodate her own interpretation was unsurpassed."[77] Urban male performers included popular black musicians of the era, such Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy and Leroy Carr. An important label of this era was the chicagoean Bluebird label. Before WWII, Tampa Red was sometimes referred to as "the Guitar Wizard". Carr accompanied himself on the piano with Scrapper Blackwell on guitar, a format that continued well into the 50s with people such as Charles Brown, and even Nat "King" Cole.

Classic blues

"Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, who was born in Columbus, Georgia, on April 26, 1886, typified the first generation of blues divas. Together with her husband Will ---or "Pa Rainey" as he was sometimes called---this immensely popular artist toured the South as part of a traveling minstrel show. She recorded extensively in the mid-20s, and her throbbing contralto voice graced over one hundred records during a five-year period. In stark contrast to the country blues singers, who usually accompanied themselves, Rainey recorded with some of the finest jazz musicians of her day, including Louis Armstrong and Coleman Hawkins. Her career also reflected the sharp difference between the informal blues stylings of the Delta and other rural areas and the polished stage presentations that marked the classic blues as commercial fare for a mass audience. The Delta musician often traveled with little more than a guitar in hand; in contrast, Rainey brought four trunks of props, backdrops, lighting, and other show business trappings, as well as a lavish array of costumes and fashion accessories. Rainey's performances served to entertain, indeed to dazzle; they incorporated humor as a characteristic element; and they revealed a more overt connection to the popular music, minstrel shows and jazz of the day... Rainey's recordings span a scant half-decade. Like many musicians of her generation, Rainey's career was irreparably hurt by the barren economic prospects of the early 1930s. In 1935, Rainey retired from performing and returned to her native Georgia, where she became active in the Baptist Church. She died in Rome, Georgia, on December 22, 1939." (Gioia:The History of Jazz)

"Bessie Smith, a protegée of Rainey's, stands out as the greatest of the classic blues singers. Born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, probably on April 15, 1894 (although the 1900 census gives an 1892 date), Smith began singing and dancing on street corners fro spare change around the age of nine. In the midteens, Smith went on the road as a member of Ma Rainey's touring show, and though Rainey has often been credited as a mentor and teacher to the younger singer, the exact extent of this education is a matter of conjecture. Smith's deeply resonant voice was probably evident from the start and may be the key factor in getting her the job with the Rainey troupe. On the other hand, Rainey's skills as a performer, as well as her mastery of the blues repertoire, must have been an inspiration to this teenage newcomer to the world of traveling shows.

Smith soon came to surpass her teacher in the variety of melodic inventions, her impressive pitch control, and the expressive depth of her music. Inevitably the younger vocalist decided to leave Rainey to further her own career, and was initially employed as a singer for Milton Starr's theater circuit, the infamous TOBA..... as a TOBA artist she she joined Pete Werley's Minstrel Show, where her pay, at least initially, was as little as 2.50 US a week. However, in 1923, Smith's recording "Down Hearted Blues" boosted her to widespread fame; the record reportedly sold over a half million copies in a few months, and soon Smith was recording regularly and performing for as much as 2,000 US per week. She toured extensively, entertaining audiences in large venues----tents set up on the outskirts of town as well as in downtown theaters-- in the South and along the eastern seaboard." (Gioia)

"Bessie Smith, a protegée of Rainey's, stands out as the greatest of the classic blues singers. Born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, probably on April 15, 1894 (although the 1900 census gives an 1892 date), Smith began singing and dancing on street corners fro spare change around the age of nine. In the midteens, Smith went on the road as a member of Ma Rainey's touring show, and though Rainey has often been credited as a mentor and teacher to the younger singer, the exact extent of this education is a matter of conjecture. Smith's deeply resonant voice was probably evident from the start and may be the key factor in getting her the job with the Rainey troupe. On the other hand, Rainey's skills as a performer, as well as her mastery of the blues repertoire, must have been an inspiration to this teenage newcomer to the world of traveling shows.

Smith soon came to surpass her teacher in the variety of melodic inventions, her impressive pitch control, and the expressive depth of her music. Inevitably the younger vocalist decided to leave Rainey to further her own career, and was initially employed as a singer for Milton Starr's theater circuit, the infamous TOBA..... as a TOBA artist she she joined Pete Werley's Minstrel Show, where her pay, at least initially, was as little as 2.50 US a week. However, in 1923, Smith's recording "Down Hearted Blues" boosted her to widespread fame; the record reportedly sold over a half million copies in a few months, and soon Smith was recording regularly and performing for as much as 2,000 US per week. She toured extensively, entertaining audiences in large venues----tents set up on the outskirts of town as well as in downtown theaters-- in the South and along the eastern seaboard." (Gioia)

Boogie woogie

Boogie-woogie was another important style of 1930s and early 1940s urban blues.[78] While the style is often associated with solo piano, boogie-woogie was also used to accompany singers and, as a solo part, in bands and small combos. Boogie-Woogie style was characterized by a regular bass figure, an ostinato or riff and shifts of level in the left hand, elaborating each chord and trills and decorations in the right hand. Boogie-woogie was pioneered by the Chicago-based Jimmy Yancey and the Boogie-Woogie Trio (Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson and Meade Lux Lewis).[79] Chicago boogie-woogie performers included Clarence "Pine Top" Smith and Earl Hines, who "linked the propulsive left-hand rhythms of the ragtime pianists with melodic figures similar to those of Armstrong's trumpet in the right hand."[75] The smooth Louisiana style of Professor Longhair and, more recently, Dr. John blends classic rhythm and blues with blues styles.